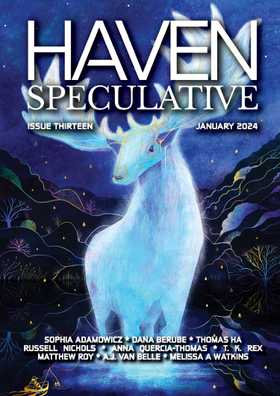

FICTION

Behind the Gilded Door

by Thomas Ha in Issue Thirteen, January 2024

There’s something wonderful about drinking during the peak of the summer heat back home—the way my skin beads with sweat and raucous laughter hangs in the air like a cloud. When we gather to talk about the old days, huddled at the benches outside the Wandering Leaf, I almost start to forget that I ever left Calathede, and I wonder what it would’ve been like to spend all of my young adulthood within the walls of the castletown. A different world where I hadn’t touched parchment or ink and instead, like everyone else, married the first person I kissed and squeezed into a home filled with the squalling of little ones and peals of tiny laughter too. A whole lifetime that flickers and dies in the span of moments, somewhere in the depths of my idle imagination.

Only Darrow suspects that I’m having second thoughts about the magi.

He stares into his tankard when I talk about the university and the year I still have before my convocation rites, and then his eyes rise to mine in a kind of silent warning, much like when we were boys and he’d spot a blackhelm pacing the market stalls hoping to beat one of us for some imagined slight. Even after all this time apart, it’s like he can see the daydreams I harbor about Calathede and would sooner crush them under his boot than let them flourish and entangle me like the creeping vines they are.

On late nights, when most of the others have stumbled home, Darrow and I will sit at the crumbling eastern ramparts, looking out past the far-reaching flatfields, and he’ll ask me about the Rotunda of Fallen Saints and the Living Library, or maybe about what it’s like to meet a real magus blessed with element from Beyond, instead of village cozenmen trying to pass folk medicine for craft. And I’ll often feel a pang, never knowing if talking at length makes me seem arrogant. Or if it’s worse when I touch the truth—that the study chambers and bookwork can be frustrating, isolating, and cold. That I’m an ingrate who sometimes wishes I had never been there, the morning when the diviners’ wagon came along the king’s road.

In those moments, when I want to talk about anything but the magi, I think of asking him about the strange things I’ve noticed since returning to my hometown, like the gilded door. But often, before I work up the nerve, we’re interrupted by the Peace Bell ringing from the castle ground, those clangs reverberating through the cobblestone streets and narrows between huddled houses—a reminder to say hushed goodbyes and hurry back out of the still heat of the summer night, where dark and familiar silhouettes gather at the archways between the districts.

#

In some ways, I realize that I prefer time on my own, when the boys are down at the quarry and I can while away the afternoon hours just outside Calathede’s walls at the banks of the Quietwater—where I wade in the shallows among the minnows and rainbow trout, remembering how the old pondkeeper would pay us each a copper mark for every crestfin we’d catch with our tangled-twine nets during the muggy summers like this one.

Now, there’s no need for any mud-splattering and net-throwing.

I’d need only flick my wrist to direct some minor current of element and levitate one of those gasping, spine-arched crestfins, still viciously snapping its toothy maw up at the sky.

And it would be easy here, I realize, to craft and cast if I were so inclined. Because for all of its rugged, barren land, Calathede seems to have abundant slipstreams of element from the Beyond, something I could never have appreciated as a child. Waves of it flowing in every direction, bleeding heavily into the world from the Beyond like an undulating web. And the heat’s so pregnant with it that I don’t even have to draw too intently before hundreds of currents bend and redirect through my hand, ready for me to shape other energy or matter however I like.

There’s so much that when I’m not careful, I can feel that painful prickling in my muscles, of the inflammation and detritus building within my blood, and I have to remember to stop before my body’s taken in too much.

Still, there are times when I indulge, like when the boys pester me to show them what I’ve learned, maybe when we’re making the sundown walk to the moiling districts or have taken our bench outside the Leaf in the heavy wetness of a sleepy summer evening. Then, I might play with the element for their amusement, float a coin above my palm where they can snatch it from the air or perhaps summon a crackling flurry of sparks above someone’s head, to their howling delight.

But when I let this go on too long, I can count on Darrow to give me that look—the expression of concern that asks, Why are you doing this? And that’ll get me to wave off the element swirling in my palm and grin sheepishly into my honeywine.

Darrow will often speculate aloud about what I’ll do after I wander about during this last free year of mine. He knows most students spend the year debauching themselves in the long night cities or studying the craft in the marshland ruins, but that I have chosen to come back here of all places. He’ll prod and press, wondering what I have in mind once I undergo the rites, take the robes, and swear my oaths. He’ll ask about the big things that lie ahead, like which of the seven sects I’ll align with and what my role might be, or where in the kingdom they’ll send me and what kind of craft I’ll practice—all the questions the other university students rehash endlessly, like self-satisfied cats cleaning their own tender little paws.

But I pretend to ignore him and go on with my drinking until the group naturally drifts back to the humdrum conversations I came to Calathede for, the good and easy summer talk—like who’s gained weight or who’s losing their hair, or who’s had a baby or doing well for themselves in town.

And we only really stop mid-drink every now and again when one of us hears the rustling of chainmail from some nearby alley or the shouts for mercy of someone being dragged, their heels slapping against the cobblestones. Or maybe it’s that heavy clang of the Peace Bell that gives us pause, a sign that the Man Up in the Towers and his blackhelms have finished seeing to someone—that awful sound that barely covers the screams of some soul being beaten or skin-stripped, somewhere in the distance.

And when it finally passes, the last toll emptying into a thick silence, we usually find a way to turn back to the honeywine and let the rising din at the Leaf wipe away any lingering feelings of unpleasantness there may be.

Eventually, in the warmth of those aimless summer evenings, I think I’m almost able to forget the weighty steps of the relentless and oncoming future.

#

And yet, more and more, there’s an uncomfortable itch in the back of my mind—a tendency toward curiosity that Darrow always said was the source of our childhood misadventures.

I suspect it’s only been enhanced by all that time in the underhalls and element laboratories, hours learning about nature’s adoration of patterns, in the anatomy of beasts, weather cycles, and so forth, so that we might gain an understanding of the iterative waves of the element Beyond.

It makes it difficult to look over the rest of Calathede again without noticing the repetition. In the boys I grew up with, who resemble and gradually replace their lumbering fathers in the quarry teams. In the warehouses in the mason’s district that burned down, only to be remade with the same arches the builders here use in every other structure. Even the old drunks who used to pick through the church coffers have all passed, but I still recognize the new ones who’ve taken up the role, with reddened cheeks and glassy eyes and stories about their bad luck that I’ve heard so many times before.

It’s all just a pattern and flow, in people and everything that we touch.

And it’s the pattern that makes it all the more noticeable that something has changed in Calathede as of late. Like the palpable unease hovering in the seasonal heat, or the whispers, the fast-shut doors, and the stares from the guards at the inner portcullis, which never opens to commoners like it used to.

And then, of course, there is the gilded door.

The first time I ask Darrow about it in earnest, we’re at the banks of the Quietwater, sweating under the blinding afternoon light at its peak.

“What are you even going on about, a door?”

“It’s just something I had heard in passing.”

“From whom?”

Darrow’s eyes follow mine so closely that I have to look away.

“Barely remember. You know. Just idle chatter. That’s all.”

I’m not sure whether he believes me, or if this is like the other times when he can see through to my heart. But the how and why of the gilded door is not something I want to describe, because, in truth, it’s not something I heard so much as accidentally discovered, during one of my first nights back in Calathede.

A night when we’d been at the Leaf far later than was prudent, and I’d begun wending my way back to my lodging, when I first felt that shivering tingle, the kind that always precedes someone unpleasant approaching.

And I knew, then, before even glancing over my shoulder, from the unhurried steadiness of the steps and the shuffling of metal, that it was one of them, a blackhelm.

There’s just a specific smell, of rust and filthy leather, that brought back all kinds of sensations I thought I’d long buried deep: sweet blood on my tongue from cuts that were slow to heal, the tender throb of bruises across my body, and the stab of every labored breath pressing against cracked ribs.

It all came back that night as the blackhelm drew closer, keeping his visor down, as they all do, leaving only the infernal faces of foul creatures molded into the helm to gaze upon—this one of a beaked devil, mouth drawn back along his visor in hollow laughter. And piss-drunk as I was, barely able to keep my sight straight, let alone stifle the rising panic at my throat, I braced myself for something, anything, to come—a glance off the cheek maybe, or a fist to the gut.

Something to say, “Welcome back to Calathede, boy.”

But instead, I found only quiet, because the blackhelm went still, stopping as though he recognized me. And it wouldn’t have been hard, I realized, to know me—the only child chosen by the diviners from this backwater in a lifetime or more. Even though I hadn’t earned the robes, I had to imagine that a local peacekeeper wouldn’t want to be the one to cross a servant of the king—to bring down on this little town all that might follow as a result.

The Man Up in the Towers and his blackhelms may have had a grip on everything within Calathede’s walls, but a low-ranking baron and his men couldn’t stop the outside world from intruding if they made some mistake with me here.

Part of me now wishes I could’ve relished the moment a bit more—this looming figure that once haunted my childhood trembling with visible indecision. Less of the terrifying, ruinous monster that I remembered and more of the confused thug I now know them to be.

But just then, without warning, a bright flash from his mind appeared in my own—a rarity that I’d been told occurs when ambient element is thick enough in the heat and air to transmit essence between magus and man, like the crackle of static in a storm.

I had never experienced this kind of transference before, so I was surprised to find that it wasn’t so much a thought that moved between us as a strange and unrecognizable image: the outline of a gilded door in a hallway lit by torchlight, decorated with golden leaves and intricately nestled brambles with such exquisite detail that each individual twig or bud appeared almost real. And the glinting curves of the decorations across the expanse of the door seemed almost to shift with the flickering of flames in the nearby sconces, too.

I felt something so sharply that my own breath seized—an overflowing terror from the blackhelm. And I could sense it wasn’t because of me, or even because of the magi I represented, but, oddly, because of what lay behind the gilded door.

Then the blackhelm pulled away, wordlessly retreating into the heat and darkness, like he’d never come upon me at all, leaving me there to wonder what it was that I’d even just seen in his mind.

I can’t tell Darrow any of this, of course, since we are forbidden from describing the use of element to others. So, instead, I direct his attention to the rippling of the Quietwater, where we can just see pale-lemon fins breaking the water.

“Do you remember the crestfins?” I ask, thinking back on the memories of those messy hours misspent. “You know, I was going through catalogs in the Living Library, must be years ago now. I stumbled on mention of them in a book, and I learned why that keeper here was always paying marks to have us catch them.”

“Well, they eat everything else in the pond if you don’t,” Darrow answers.

“That’s true. You’re right, of course.” I nod, trying not to be disagreeable. “But…what I didn’t appreciate, what I didn’t understand until I’d learned it for myself, was that the crestfins…they aren’t even really fish when you get right down to it. They may look it, when they’re young, swim in the same schools alongside the others in their first years. But in truth, they’re something else, a kind of lesser drake, brought to our waters from the marshlands at some point, who even knows when.” I toss a rock at the sickle-shaped fins at the surface and watch them scatter. “After a couple seasons, they grow those fangs. After a dozen, little legs under the belly. And then eventually, left untouched, they leave the water-bounds and affect much more than just a pond.

“Strange, isn’t it? How the balance can be destroyed by just one little thing?”

Darrow doesn’t answer, but I think he understands—that something like that is happening with the blackhelms here in Calathede, even if he doesn’t want to admit it. Perhaps it’s because he has more standing among the men in the quarry after all the years as a laborer.

I know he’s worked quite hard over time to be elevated to one of the council headmen, and I have to imagine that it behooves him not to disturb town affairs, to poke and pry at the strangeness the way I am doing.

But even if he won’t entertain this curiosity, I can’t help but believe that whatever it is that the blackhelms fear, whatever it is that lies behind the gilded door, may be something that can put some of the old balance of Calathede I remember back in its place.

“I see,” is all he replies at first, and I feel something between us, like an unseen shoal that parts the flow of a river. “You know, there are stories we have too about what goes on with the magi. Nothing as fancy as what you find in those bound books and catalogs of yours, mind you. But stories of our own.”

“More exciting than the real thing, I’d imagine.”

“Probably so,” Darrow nods. “But even simple and ordinary people notice things if you give us time. Like how the life of the magus isn’t all fame and the fantastic. How difficult and…burdensome a higher loyalty like yours can be. If I knew I were to bear something like that for the rest of my life, I might distract myself too with summers and little towns and peculiar doors.

“But I think it would be best,” he says intently. “To leave things in Calathede as they are and focus instead on what lies ahead of you out there.”

We watch the sickle shapes gather at the surface again, and I push aside the unease between us with a smile so that we might enjoy this afternoon.

#

I know of course, without Darrow, that I need to turn to others. But one of the better things about growing up in Calathede is that you can’t go for more than a minute’s walk without finding someone who knows you or your kin. In this case, it’s my mother’s oldest friend, a seamstress in the western block, who has a son about my age. And I seek him out, knowing that he’s worked the castle grounds since we were boys.

It doesn’t take much prying to get him to let me into the outer yards—I go on about wanting to know what it’s like working the way he does since I might one day be positioned in a castle after the rites. And maybe it’s the shine of the magi or an affinity for my family, but he’s happy to let me peek if I promise to be careful, though he cautions that he doesn’t have access to the inner bailey or anything of interest.

Apparently, the Man Up in the Towers has stopped letting servants into the castle proper. Only physicians and blackhelms move freely anymore. I tell him it’ll only be an hour in the morning, while the blackhelms are still passed out in pools of ale and piss. So, he looks the other way when I step in through the outer walls and skulk along the corridors.

From the flagstone, there’s no doubt in my mind that this was the interior I’d seen in that image of the gilded door. And if I’m honest, there’s an excitement from slinking about, an untouchable feeling when there seems to be no one to stop me. Perhaps that’s why, when I reach the inevitable point where I can go no further—a locked passage that would take me to the main hall—I’m a little too hasty in drawing the element to open the way.

The casting itself is simple, a manipulation of the tumblers to press in a way that mimics the teeth of a key, but there’s a sharp and familiar pain, like cartilage popping in the edges of my wrist, when I direct the waves of element through my body. And though I’m delighted to see the door sigh open once the cast is complete, my fingers tremble as bits of skin slough away like desiccated foliage from tree branches during the harvest season.

This kind of poisonous reaction happens, of course, from holding too much element in the body for too long. And it’s my fault, really, for not slowing the rate of my draw to account for the density of element here. But I also know that I will recover eventually, as all magi do, no matter how uncomfortable and unsightly the detritus may be, so I ignore the yellowing mucus that forms along the inflamed creases of my hand and continue ahead, gradually realizing from the echoes below that I’ve come to a pathway that crosses over the castle’s sunken gaols.

When we were young, me, Darrow, and all of the rest, we’d scare each other with stories of the belly deep beneath the castle. There were tales from long before we were born, back when the Man Up in the Towers lost his sons in the wars with the western sovereign beasts, about how he would drag men here by the dozens with little warning or justification—all of the groups and little gangs running the corners of the castletown. How they took anyone whom the baron and his blackhelms thought threatened their control in Calathede in those days—the mire-men, the ballasters, the weaponeers who used to call themselves the Calvin’s Boys.

They all eventually ended up in the sunken gaols, never to emerge again.

I suppose I’m not sure what I expect to hear coming from the staircase that disappears below, perhaps screams or the splatter of bile like we always used to tell each other about, but it’s only faint shudders and muted cries drifting from somewhere beneath my feet. Many of them, I imagine, from people I must know, even if only through tenuous memories. Hard as it may be, especially with some of the voices that sound so young, I remind myself that I’m here for something more and leave the whimpering back there in the dark.

By contrast, the main hall is silent when I come to it, almost peaceful, with sunlight playing about in the windows. The carpet’s ripped to pieces, strewn about as though someone decided they couldn’t stand the sight, and there are burns scarring the tapestries and spots on the floor, like a rash of smoke stains, empty barrels and the faint scent of drunken sick lurking about. The blackhelms have really had a run at the place, I tell myself, and the exclusion of the servants is showing itself the deeper I go.

It’s a precaution more than anything, since I can sense no one about, but I draw the element again, carefully, to cast a thoughtslip around my body—that way, should anyone stumble upon me, they’d have trouble perceiving me there, forgetting my presence the moment they tried to grasp it.

My hand drips more of the lemon-colored detritus, a jellied layer oozing around my forearm now, while I pulse the element, steadily, gently, maintaining the thoughtslip about me as I move toward the upper areas of the hall.

I already have my suspicions about what I’ll find. Because the shambles here paint a clear picture of a lord that’s fallen to pieces, whose disordered mind is reflected in every corner. Without visiting commoners to question or press their noses about, it would be easy for the blackhelms to hide the old baron’s condition and let his paranoid senility run its course like this behind closed doors. I assume The Man Up in the Towers barks orders like the deranged despots in old stories, riddles of madness and outrage at his imagined enemies, while the blackhelms do whatever’s necessary to appease him. Or maybe, more likely, the blackhelms just go on and do whatever they want, unhindered by anyone’s watchful eye.

Whatever the deteriorated state of the Man Up in the Towers, I anticipate I’ll know soon enough, because right where I should find the entrance to the upper chambers, I come upon the gilded door, just as I remember it from the blackhelm’s mind—the golden leaves and brambles, the intricately carved detail.

The burning detritus expands to my chest, and I feel at the back of my tongue some of the mucus beginning to drip down my swelling throat. But I’m impatient to know what’s being hidden, just out of reach, and so I’m not as measured this time with the next cast—pulling the gold leaves and vines as the weight of all that metal relents and the gilded door eases open with the force of all the element I greedily direct through my body.

What will happen when I confirm my suspicions, I wonder? Will the magi laud me for ferreting out the abuse—for catching lowly blackhelms running rampant under the false color of authority? Maybe the king’s court will recognize me for it, reward me—I’ve heard magi sometimes gain titles in exceptional circumstances.

Each stone step I ascend, I think to myself, wouldn’t it be fitting—after those years spent running and hiding as a boy—that I might be the one to break the clawed hand the blackhelms hold at the throat of Calathede. To return here in glory, to show them all.

I draw close to the end of the staircase and stop.

The morning sunlight heats the stones around me, and I can smell it—like baked sickness, reminiscent of the canals outside the capital where the waste buckets are dumped. I nearly gag, with the detritus spilling from my lips as I cough, and I can barely see through the stinging in my eyes, either because of the putrid air in the tower or the mucus beginning to slough from my brow, as the flesh there loses its shape.

This is where most would turn around, I know—when it’s clear what I’m going to find if I keep going. Maybe Darrow was right about my curiosity, my inability to stop, I think as I push past rippling curtains and into the brightly lit bedchamber, burning as summer sun beats through the windows. There are strip-cloths and bowls everywhere, like the water vessels when it rains in town, but stained with streaks of brown and black. And as I move further, I wave away the dark clouds of insects, thousands of them, crawling on the walls and the floors. Their buzzes all begin to join in something that sounds like a rising roar.

I can barely breathe in that heat, the sweat on my face mixing with the detritus, now spilling from my eyes like thick tears while the lumps of my cheeks blister, bulge and bust like bloody blooms, but I know myself enough to know, especially now, I have to look.

And when I do, when I finally work up the nerve to see what’s being hidden, the thing that ignited the fear in the blackhelm who saw me that night, I can’t even really make it out—whatever it is that’s left in the bed. The mass of flesh that looks like it could have been a body seems half melted into the sheets, neither solid nor liquid, a mix of rendered fat and skin, a sludge at the edges of the bed. So many things crawl along what might have been the orifices, pupating, flittering in and out of all the putrescence.

I want to scream then, to release some of the terror I feel in the hollow of my chest, but I can’t for fear that the glistening flies, already swarming the rivers of pus and detritus over every part of me, will find their way into me too.

#

“All will be well.”

I see Darrow’s boyish face again, as I have many times in my delirium—the way he looks on that day when the masked diviners encircle me and touch pristine moonwell metal instruments to my forehead, before murmuring in something that sounds like agreement. That shivery, cloud-dimmed morning when their soldier-escorts order me and my parents to step away from the townsmen and into their covered wagon.

Darrow’s the only one to rush from the other children waiting to be tested. An embrace and a whisper, only for my ears.

“All will be well,” he tells me. “We’ll wait for you here, no matter what happens. We’ll wait for you to come home.”

Every part of me writhes when I wake in the darkness of my lodging, heavy curtains shutting out the blazing of summer coming in around the corners. I can tell, without touching my cheek, that the detritus is still flowing out of me and into the bed. I barely recall stumbling out of the grounds and back, hiding my misshapen state under my cloak. I was lucky to have made it to safety and out of the light.

It takes me a moment to realize Darrow’s there with me too, patting a damp towel to my brow. He does not turn away from what the element has done to me and looks on with what I interpret, at least at first, as concern.

And before I can get to anything else, before I bother to explain what I’ll need him to procure so that I might hasten my recovery, I sputter out what I saw when I went wandering the castle ground and looked behind the gilded door.

It is only when I have finished that I notice the heaviness in his eyes. A cold withdrawal and solemnity in the shift in his expression. No fear, no surprise, about all that I had found. A grimace and silence and stillness—until I come to realize the truth.

He already knows.

Darrow wrings the cloth, and then, when he’s ready, smiles hesitantly, like he doesn’t know how to tell me. Like I’m a child who doesn’t yet understand that a beloved pet is gone and will never come back.

“Nothing good ever happens to lordless towns,” is what he says. “Especially ones in the middle of nowhere, without resources to trade. No one wants title to land with barely enough soil to till and a quarry that will likely be empty in a handful of years. No.”

He speaks now in a measured way, not at all how he does when we’re all together at the Leaf, but more how I imagine he handles himself on the quarryman’s council, when there’s business at hand.

He tells me the council and the blackhelms are close to reaching terms with the local barony to figure out what happens to Calathede now that the Man Up in the Towers is gone—some arrangement where they’ll give something from quarry proceeds for the right to name a castellan of their own to administrate the town. And that way, they don’t have to worry about that lawlessness that comes when a township has no line of succession. And just as that’s finished, when the way of things is secure for a path ahead, that’s when it will be more widely known, spoken of, the untimely end of the Man Up in the Towers.

Or so he says.

“But…if the baron is dead, the king…” I begin.

“Still has no interest in involving himself,” Darrow finishes. “So long as the local barony vouch for our castellan and the crown gets its tax. What difference is it to his coffers if it’s one yokel filling them or another.”

Each time I speak, the thickening mucus in me catches, and I’m unable to interrupt, to tell him the folly in what he’s saying. That even if any of that were true, even if there were a way forward for Calathede without the Man Up in the Towers, the blackhelms cannot be left unwatched. I can still hear voices in the goals, their whimpers somewhere in the room.

But as if reading my heart, he answers in his own way.

“Do you think they don’t already know?” Darrow looks over my disfigured face. “Think hard about how quickly secrets flow across every crook and crevice of Calathede. Then consider whether everyone out there really doesn’t suspect what’s happening in the castle grounds, in those chambers, behind that gilded door.

“We pretend the Man Up in the Towers is watching us, the same as he ever was. Because we have to, to survive. Pretend and carry on, just the same as you.”

In truth, I don’t fully understand what he means, and I don’t get a chance to ask before he gets up from the chair. But the last thing Darrow tells me, after warning me to leave Calathede as soon as I can carry myself—before the blackhelms decide they can’t risk anything going beyond their walls—is that he’s sorry.

“I want nothing but the best for you,” Darrow says. “I always have. And I hope you find it, somewhere, with the magi or otherwise. I hope you find what you need out there.”

Out there, he says.

And when the door closes, my mind turns over in the sweat and heat—every bit of my skin in that summer oppression swelling and weeping. I try to lift my body and find everything spinning along with my thoughts.

My half-conscious mind flickers in and out across too many points in time, while my body tries to pull itself together, little piece by little piece. I keep thinking of honeywine at the Leaf, that sensation of syrupy liquid quenching this aching somewhere deep in my chest. My friends egging me on, clapping for just another trick or two, just a bit more element again to get them to laugh. Or all of us, just gangly boys, hustling along the market stalls and across thatched roofs or mucking about on the muddy banks of the Quietwater.

With those slippery little crestfins—one of them twisting and biting at my wrist in the shallows before I fling it to the ground, watching it gasp as a younger Darrow raises a stone and crushes it to pieces, remains of blood and lemon-colored scales strewn across the patches of grass and dirt.

It’s then in that whirl of memory and sickness that I realize the disruption in the balance, that tear in the fabric of Calathede I’d been seeking. It wasn’t the blackhelms and their violence, not the Man Up in the Towers and his cruelty, not Darrow or the council or their dealings to keep this castletown going.

It was me.

I’m the disruption.

And amidst those scattered recollections, in all of that heat and nausea sizzling in every bit of my body, I understand what Darrow meant when he said I’d been pretending.

Pretending that I have somewhere to return to, where there are people to embrace and who whisper that they’ve been waiting for me all this time. Pretending that there might be another life somewhere, away from the capital and the magi and their plans and their rules, away from the pain of the element passing through our bodies and solidifying into waste and detritus, poisoning us over and over and over again. Pretending I might have some place in a timeless castletown where the pattern and flow of our lives never have to change if we decide we don’t want them to.

Pretending that it’s not just misremembered fragments and half-hearted hopes of a scared boy carried away from his home that once, even for just a short time, I really did belong somewhere.

But the tolling of the Peace Bell thunders over the town then, filling my ears and everything in that room as I drag myself downstairs, drenched in sweat and filth. Each clang echoes in my head as I stumble toward the sundown skies, shuffling over cobblestones and around corners, keeping my flattened face in the dark of my hood, my nose and under-eye skin splitting from the weight of draining detritus—every bead of perspiration in that muggy heat feeling as though it’s pulling my melting flesh away from the solid beneath. And under the last of the mind-shattering clangs, I think I almost hear them, those helpless whimpers from the gaols, somehow rising up, impossibly, from the very stone and soil.

With every step amid the dark shapes that I imagine are watching me as I falter on the king’s road toward the flatfields, farther and farther from the cracked corbels and towers stained with raintrails like whitened tears, farther and farther from those huddled homes and the talk and the laughter in the public houses and across the archways, it all begins to feel like a lost and fevered dream.

All of it, Calathede, just some foolish and forgotten dream.

And with the dreaming done and forever behind me, I must face what remains, now that it is time, finally, to wake.

© 2024 Thomas Ha

Thomas Ha

Thomas Ha is a former attorney turned stay-at-home father who enjoys writing speculative fiction during the rare moments when all of his kids are napping at the same time. Thomas grew up in Honolulu and, after a decade plus of living in the northeast, now resides in Los Angeles.