NON-FICTION

Interview with Terese Mason Pierre

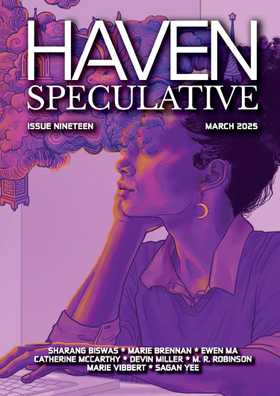

by Leon Perniciaro in Issue Nineteen, March 2025

Leon Perniciaro: How’d you get involved with Augur?

Terese Mason Pierre: So I live in Toronto, spent most of my life here, and I went to the University of Toronto for my undergrad. And while I was at the University of Toronto, I was involved in a number of student groups. By the time I was in fourth year, I was in two choirs, directing one of them. I was volunteering at a hospital. I was doing so many things. And among the things, I was a poetry editor for a student journal called The Spectatorial. It was the only genre magazine on campus, and I worked as a poetry editor on that magazine for about a year. I worked with poets and got to see some of their editorial and submission processes. And when the people who founded Spectatorial graduated, they founded Augur. I started as a poetry editor for about 3 or 4 years, then I became a senior editor of poetry, and then in 2021 I became co-editor-in-chief alongside Lawrence Stewen, who’s also a writer. We have recently undergone a restructuring of the journal, and the some of the fixed roles have been dissolved. Now, each issue of the magazine will be led by different people. So it’s more of a collaborative collective process. Now, my role is in programming. I’m the Chief Programming Officer of the non-profit, the Augur Literary Society. My job is to create all of our programming and partnerships. I lead AugurCon, I do workshops, and I help people develop their own programming. I also write grants. I’m a programming grant writer.

LP: I don’t know how extroverted people see the world, but it comes through in all of your activities here. You’re too busy. You have too much that you’re doing, right?

TMP: This is kind of my reputation. I don’t know how I feel about it anymore. I like having things to do because it’s fun. If I get to talk to people, it’s great. But I’m also very tired. I do identify as an extrovert, but that just means that I like being around people. I’m also very shy. If you put me in a room full of strangers, I’ll stand by the wall, and hope really hard that someone comes and talks to me. But I love being around people. It’s great.

[Then we talked about a whole bunch of things that didn’t quite translate but were a joy, ending with me giving a long-winded explanation about how to pronounce my name.]

TMP: I ask because people pronounce my name wrong all the time. It rhymes with the Spanish Perez, but with a T. My name is French and it also has accents, but I don’t use the accents. I didn’t like my name when I was younger, cause it was so hard. People just could not spell it and they could not pronounce it. But as a writer now, I’m like, this is a great name.

LP: It’s got gravitas. What do you like about your name?

TMP: No one’s ever asked me that before. My parents are from the Caribbean, from Grenada. My mom named me after a friend of hers. I think it was the first female prosecutor in Grenada. I think she died pretty young, in her thirties or forties. But she was good friends with my mom. So, she named me after her, and my name is French like my dad’s. They all have French names. And my name means something like Reaper or Harvester.

LP: Why am I starting to get a little emotional? No, that’s good. Every good interview should have us both crying at the end. We’re getting down to the serious stuff here. I feel like all of this kind of leads into another question I had about Augur.

[Then I launch into this long-winded thing about getting tested for ulcers for some reason? Terese is a saint to listen to this. Until finally:]

LP: I know that Augur has a really specific focus on Canadian writers, but also on Indigenous writers. I’m just kind of curious to know what the impetus for that is and if you think there are pros and cons to having that kind of focus.

TMP: So, Augur has three founding pillars. First is we aim to publish, prioritize, and showcase the work of marginalized and underrepresented creators. We are aware of what the dominant culture is like. When you go up to the top and you see who really has the power, it’s still mainly white and straight, and so we want to make a space for those marginalized creators. We want to pay them pro rates, and we want to bring those diverse voices to an international stage. Secondly, funding stipulations are that we publish 75-80% Canadian content. We are Canadian, so we are invested in Canadian and Indigenous literature, specifically Canadian speculative literature. But also, because we are sort of a bigger, more reputable magazine, we’re able to bring those Canadian and Indigenous writers to an international stage as well. We want to make sure they get nominated for awards and that they’re getting visibility. The third pillar is that we want to provide programming that’s specific to our communities. We want to be a community hub, a leader in Canadian SF literature. I find that a lot of SF groups are very insular. So, we want to be that network. We also have a majority marginalized staff, because the people on staff reflect what is published in the journal.

LP: That’s very cool. I can’t think of another big SF magazine that has such a focus, and I think that’s really valuable.

TMP: Yes, and we separate Canadian and Indigenous content [in our calls for submissions] because not all Indigenous peoples within the borders of Canada identify as Canadian. But if they live in Canada, we count them as part of our Canadian quota. And we’re also open to Indigenous writers who are not from North America.

[Then there’s a bit where I talk about my academic research, and Terese gives me some really great suggestions for scholarship because she knows her stuff. And we end up here:]

LP: I recently read an article by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang about how decolonization is not a metaphor but a real process. Does that kind of terminology appeal to you?

TMP: Okay, so, at AugurCon 2020, I very last minute—maybe a day’s notice—had to moderate a featured conversation between Joshua Whitehead, who is Indigenous, Jael Richardson, who is Black, and Larissa Lai, who is Chinese Canadian. And one of the points that Joshua Whitehead brought up that I found really interesting was that what we consider speculative, what we consider fantasy—that delineation between real and unreal—is 100% colonial, right? Europeans have various modes and systems around what is real and what is not real. There are all sorts of things that, from a Western fantasy literature standpoint, might be “made up,” but for other cultures, it’s a very real thing. So, I think about what that means for what we publish and the kinds of storytelling modes, the narrative systems, that we are platforming—the politics of it. What do we want to hold as real? What does it even mean to call someone a speculative writer? The writer may be like, What I’m writing is not speculative. To me, it’s real. So, we have to be careful about how we talk about their work and how the editor edits their work.

LP: 🤩🤩

TMP: That's what I think of Augur work and decolonization, of speculative fiction work and decolonization in general. That›s how I think about this delineation between real and unreal and whose knowledge that highlights and whose knowledge that puts down.

[Then we talk a little about cons until I awkwardly transition to:]

LP: I think my last formal question is about what you’re working on. I read some of your poetry this morning while I was preparing. Are you still writing a lot of poetry or are you mostly writing fiction? What are you working on lately?

TMP: What I mainly write is literary and speculative poetry, and I’ve been published widely in that regard. My chapbook Manifest was nominated for a literary award and a speculative award. Once in a couple of years I’ll publish a short story. I’ve been doing well with that. The last short story I published also won an award. And right now I’m just working on my edits for my first book of poetry, and I’m aiming to start writing a poetry second book. I also want to finish my fiction manuscript.

I’ve written a couple of short stories, and I think about submitting them, but then I’ll have to edit them. I hate editing my own work. I hate it so much. I love drafting. Drafting is great. Outlining and drafting—beautiful. I want other people to edit my work. To read it and tell me what I need to do, and then I go in and edit it. That’s what I want. So, I have, like, six short stories just sitting on my computer, waiting for me to get the time and energy to edit them.

LP: It's funny because I think writers are the only people who are like, God, I hate doing this. But also, I can›t stop and also I love doing it. I don›t know how to describe it exactly.

TMP: I think it's very hard, but as far as that’s your baby, your lovechild—you can’t imagine life without it.

LP: Do you have anything you want to plug?

TMP: My first book of poetry, Myth, is coming out on April 1st, April Fool’s Day, from House of Anansi Press. It’s a mix of literary and speculative poetry.

[Then I foolishly didn’t ask enough follow-up questions, but you should order it

immediately at https://houseofanansi.com/products/myth!]

Terese Mason Pierre (she/her) is a writer and editor whose work has appeared

in The Walrus, ROOM, Brick, Quill & Quire, Uncanny, and Fantasy Magazine, among

others. Her work has been nominated for the bpNichol Chapbook Award, Best of

the Net, the Aurora Award, and the Ignyte Award. She is one of ten winners of the

Writers’ Trust Journey Prize, and was named a Writers’ Trust Rising Star. Terese

is an editor at Augur Magazine, a Canadian speculative literature journal, and coDirector of AugurCon, Augur's biennial speculative literature conference. She has co-hosted poetry reading series, spoken at conferences, organized literary events,

judged writing contests, facilitated creative writing workshops, and mentored

emerging writers. She is the author of chapbooks, Surface Area (Anstruther Press,

2019) and Manifest (Gap Riot Press, 2020). Her debut poetry collection, Myth, will

be published with House of Anansi Press in Spring 2025. Terese lives and works in

Toronto, Canada, and is an MFA candidate at the University of Guelph. Follow her

Instagram and Bluesky.

Leon Perniciaro

Leon Perniciaro is the editor of Haven Spec Magazine, an English PhD candidate at the University of Connecticut, and a member of the Game Design and Development faculty at Quinnipiac University. A citizen of the Choctaw-Apache Tribe of Ebarb and a New Orleanian, he now resides in New England, where he's terrified of both the climate crisis and the Great Filter. His academic research centers on the intersections of Indigeneity, race, and the environment, with a dissertation project shaping up around ideas of extraction and the various ways that settler society tries to claim Indigeneity for itself. Follow him on Bluesky @leonp.